04. Bug and Incident Management

Incident management is a basic point of efficiency within a development team. From how bugs are managed, it’s easy to tell whether or not an organization’s testers and developers feel as if they are a part of the same team, with the same goals. This assertion is not only aimed at developers, urging that they collaborate better with testers, but also at testers. Testers should avoid complaining (as they sometimes do) when a bug they reported doesn’t get fixed and must understand that not everything needs to be fixed, depending on the team’s global vision.

One poor incident management practice that we always find irksome at Abstracta is that with the hundreds of tools available for incident management, some teams still choose email as the designated channel for reporting bugs. Or worse, not using anything at all, and the tester simply taps the developer on the shoulder after finding a bug.

What’s the problem with reporting bugs without recording them with an adequate tool?

Basically, it’s impossible to follow up, keep a record, know the status of each incident (if it was already solved, verified, etc.), or even, if there’s a team of testers, have it clear what things were already reported by another tester that shouldn’t be reported again.

Of course, even when using an incident management tool, there will still be a need to speak face to face, but they do aid in adding clarification. For example, one can comment on and show directly, in the moment, what happened and thus communicate more effectively.

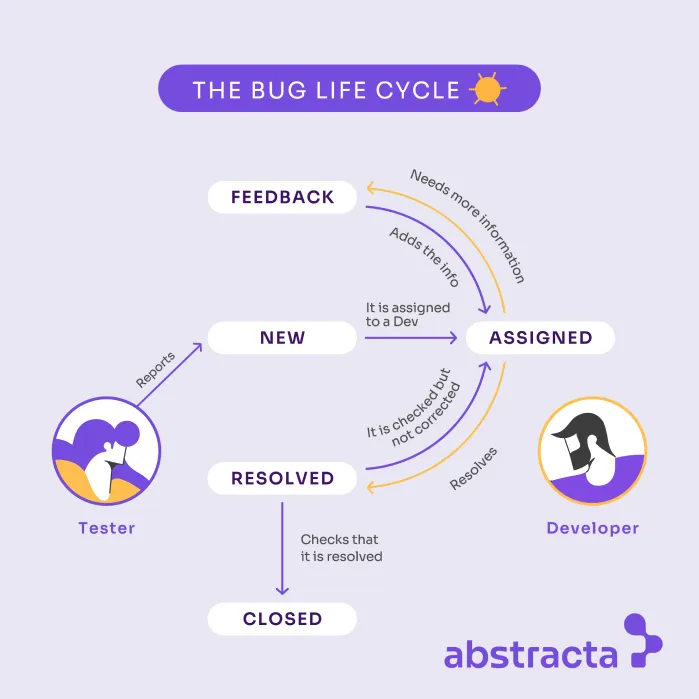

The following scheme summarizes a possible life cycle of a bug (there could be a thousand variations of this according to the team’s structure, size, etc).

One of the most typical mistakes in incident management that our team has seen while working with different companies across traditional and Agile environments has to do with the moment when a bug is deemed “fixed” and the developer marks it as closed.

It is important to remember that the tester must double check that a bug has been properly fixed before closing it!

First, the tester reports it and then the developer fixes it, but the person who should ultimately determine if it has been resolved is the tester that reported it in the first place. What if the developer thinks it’s gone, but upon further testing, it is still there? What if a new bug has been created in its place? A tester should always go back and check that the bug no longer exists in order to minimize risk.

There are several other valid variations of this scheme. For example, there could be someone with the responsibility of reviewing the incidents that come in and deciding which ones to fix and which ones not to fix. This situation could work within the flow above, whether it be the tester or the developer who marks a bug as “resolved,” “won’t fix,” or through a dialogue (via the tool or a different medium), both the tester and developer could decide together what is the appropriate decision, showing mutual agreement between the two.

At this point you may be wondering, “Why is this important for continuous testing?” As stated before, this is the main point of interaction between testers and developers, whether they are under the same roof, or in distant countries. Moreover, there are tools like Jira that allow traceability among the issues reported in the tool and code, which, in order to make the most of these features, everything must be well mechanized.

The most mature testing teams have a perfectly oiled incident resolution machine, (using a designated incident management tool) as the greatest interaction between testers and developers is in the back and forth of these mechanisms.