Don’t forget this key step when debugging software

The bug (or creature on Earth for that matter) with one of the shortest life cycles is the Mayfly, who, after transitioning into the adult stage of its lifespan, typically reproduces and then dies within just 30 minutes. What if bugs in software were born and eliminated that quickly and easily! When testers and developers work together effectively, the period of time from a bug’s creation to its elimination in software is minimal.

Although bugs can never be 100% preventable and software will never be 100% bug-free, there are good practices that teams can adopt so that bugs in software live for only a brief amount of time and never get around to multiplying. A good incident management system helps to ensure that most bugs are found and fixed well before going into production.

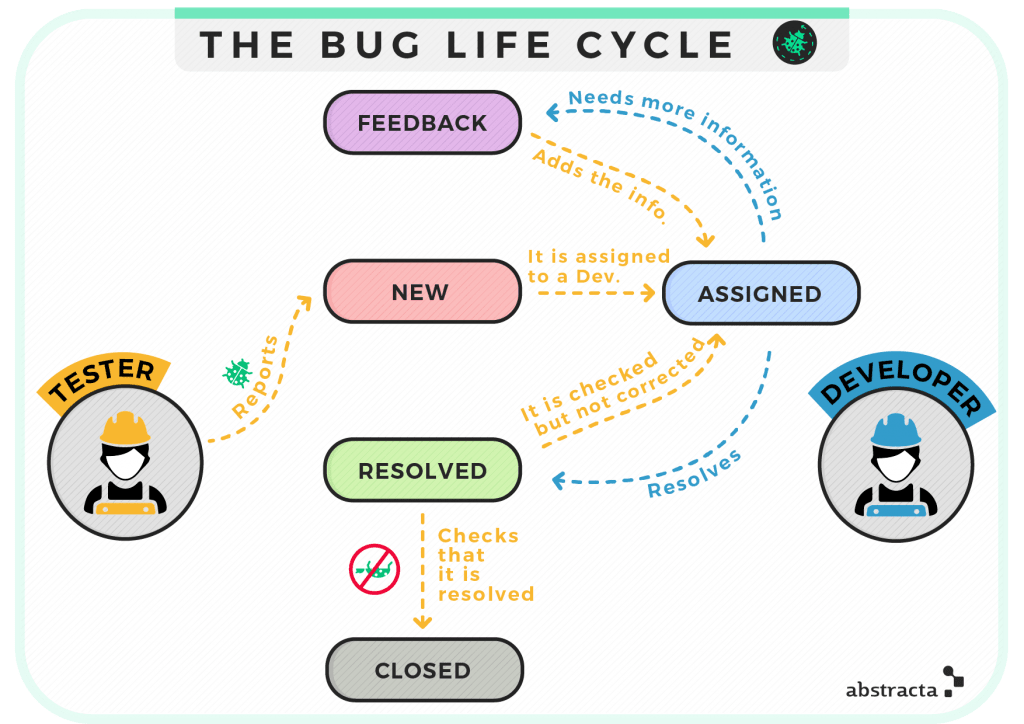

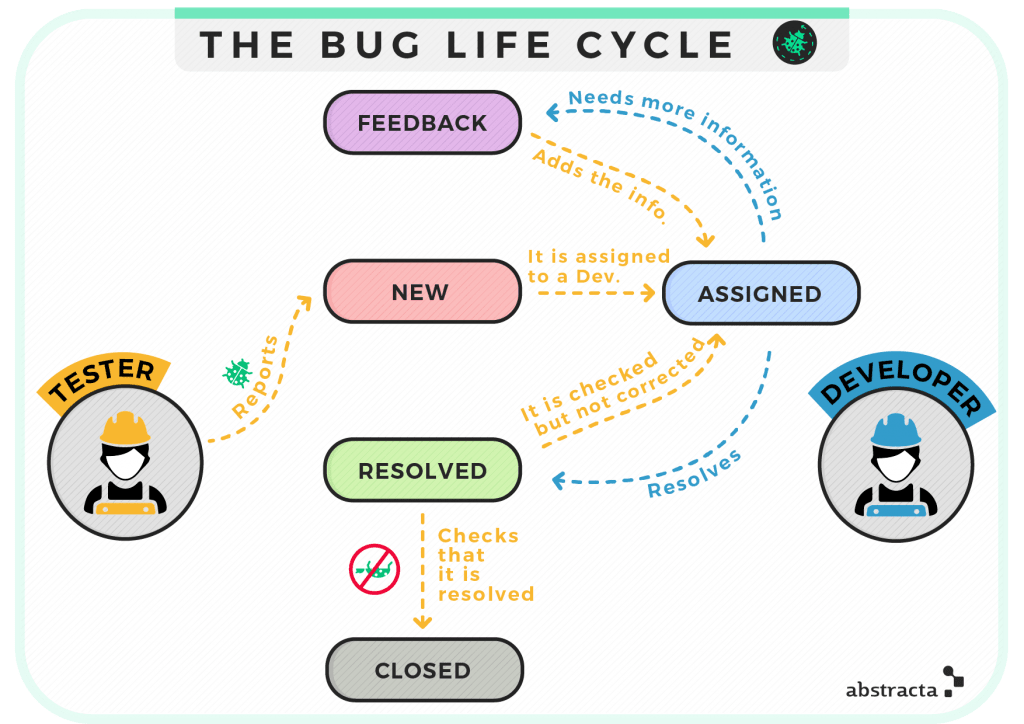

The Bug Life Cycle

This is a basic sketch that sums up one of the possible ways to represent the bug life cycle that I talked about in our new functional test automation ebook. There could actually be a thousand different variations of the bug life cycle based on the size of the team, the organizational structure, etc. but, for us, this cycle is basically law!

Where Incident Management Can Go Wrong

One of the most typical mistakes in bug management that the team at Abstracta has seen from working with different companies throughout the years across traditional and agile environments is when a bug is fixed and the developer marks it as closed. Yet, we must not forget to double check incidents! First, the tester reports it and then the developer fixes it, but the person who should ultimately determine if it has been resolved is the tester that reported it in the first place. What if the developer thinks it’s gone, but upon further testing, it is still there? What if a new bug has been created?

[tweet_box design=”default” float=”none”]A tester should always go back and check that the bug no longer exists in order to minimize risk. [/tweet_box]

Variations of the Bug Life Cycle

There are several other valid variations of this scheme. For example, you may have someone who has the responsibility of revising the incidents that come in and decide which ones to fix and which ones not to. This situation could work within the flow above, whether it be the tester or the developer who marks a bug as “resolved,” “won’t fix,” or through a dialogue (via the tool or a different medium), both the tester and developer could decide together what is the appropriate decision, showing mutual agreement between the two. In another scheme, you may want to add when to re-open an incident and what happens once it is re-opened. Or, an old bug would simply appear as a new one and start the lifecycle all over again.

Incident management is a basic indicator of the efficiency of a development team and it is additionally a key area where you can see if testers and developers feel like they are a part of the same team or not. Both sides need to do their part to work as a team. It’s not just developers who need to work on collaborating with testers, but also testers need to not complain when bugs aren’t resolved and instead share a global vision focused on the objectives of the whole team while understanding that there’s no fixing everything.

I’d love to hear your comments regarding the bug life cycle and if you follow a similar scheme or another that is more useful or appropriate for you, the typical problems you face, etc.

Recommended for You

The Software Testing Wheel

The Career Path of a Software Tester: An Infographic

Federico Toledo, Chief Quality Officer at Abstracta

Related Posts

How to Choose a Software Testing Company

Factors that will help you pick the right outsourced software testing company for you Need some help with your test efforts and are evaluating different software testing outsourcing companies? Like all things worthwhile, it will take some effort to choose a software testing company that…

How to Optimize Website Speed for Black Friday

Is your website prepared for record breaking traffic and sales? Before you know it, it will be Black Friday and then, Cyber Monday. These consumer “holidays” bring about the race for shoppers to buy all of the coveted items on their shopping lists before they’re…

Search

Contents

Categories

- Acceptance testing

- Accessibility Testing

- AI

- API Testing

- Development

- DevOps

- Fintech

- Functional Software Testing

- Healthtech

- Mobile Testing

- Observability Testing

- Partners

- Performance Testing

- Press

- Quallity Engineering

- Security Testing

- Software Quality

- Software Testing

- Test Automation

- Testing Strategy

- Testing Tools

- Work Culture